Art - Harry Wareham

A philosophy of the moving image - Samuel Mack-Poole

A philosophy of the moving image

“A self-destructive man feels completely alienated, utterly alone. He's an outsider to the human community. He thinks to himself, ‘I must be insane.’ What he fails to realize is that society has, just as he does, a vested interest in considerable losses and catastrophes. These wars, famines, floods and quakes meet well-defined needs. Man wants chaos.” – A Waking Life.

I have noticed, when looking back over my brief, brief existence that many an intellectual likes to proclaim they have read many books. Oh yes, my friends, dropping a cheeky quote here and a clever reference there is impressive when one is attempting to be a raconteur. Nevertheless, the same regard doesn’t seem to exist for film. Why is this the case?

It is fair to say that the classic medium of communication for philosophy, aside from talking, has been through the written word; or, in other words, a book. Thus, one can be a tad romantic when referring to a work of philosophy. Furthermore, books are less passive in a sense. When one reads a book, be it a work of philosophy or not, it is up to the reader to connect ideas, deduce, analyse, discover and imagine. With a film, these elements are controlled by the director.

Nevertheless, my friends, can you imagine what Aristotle, Nietzsche, Mill, or a plethora of other dead philosophers, could have done with a moving image? In the end, we can only imagine.

Film is incredibly crucial to philosophy. In fact, I would go so far as to say that philosophy’s accessibility is dependent on the moving image. Also, I think watching philosophical films should be studied side by side written works of philosophy. I cannot think of a single reason why not.

Are the debates between Lennox and Dawkins not of a high quality? If one would rather refer to a film, is A Waking Life not provocative enough? Its contributors analyse the very essence of reality – amongst educating its viewers about history, literature and dreams. And there are many, many little gems out there, too. The Three Minute Philosophy shorts by the YouTube user CollegeBinary are absolutely brilliant; I really couldn’t commend them enough. If you haven’t seen them, watch them. The videos are, quite simply, must see philosophy.

Now, I would like to discuss a film which inspired me to think of the moving image: Cloud Atlas. I really enjoyed the film, despite the prejudices I had, and maybe still have, regarding reincarnation. The film, directed by the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer, is a philosophical masterpiece. There are, quite literally, many delicious onion-like layers to this film. It’s based upon the novel by the same, written by David Mitchell, which I have just read (see, I’m clever ‘cos I reads booksies). The film is largely true to the novel.

A huge theme of the film is reincarnation. Now, I must admit that I have no sympathies with the theological/ spiritual notion of reincarnation. It’s completely illogical from my perspective – that of a scientific materialist. However, in spite of my theological prejudice, I thought the exploration of the idea of reincarnation, being the main theme over three hours of film, was very extensive. And although I came out of the cinema with my thoughts on spiritual reincarnation unchanged, my thoughts on nurture and consequentialism had been refined. One line which inspired me to think is as follows:

“Our lives are not our own, we are bound to others, past and present. And by each crime and every kindness, we birth our future.”

Whether you agree or disagree with this comment is of no consequence. From my perspective, an opinion succeeds if it is loved or hated with equal measure. However, I do think the above quote really touches on something. Genealogy is a subject which I find to be of incredible interest.

Our identities are not solely created by ourselves. We have no say as to which culture we are born in; we have no say as to who our genetic creators are. When I researched my family tree, I found that a correlation exists: many of my ancestors were highly educated. Is it then, merely a coincidence that I am a teacher? If a positive ethos towards learning has been prevalent within my family for six generations, was it almost inevitable that I would be a teacher?

And, what of me? I am only a part of the massive jigsaw that is me: the causes of me, and the consequences of me, are not entirely known to me. How very interesting! If I own my house and give it to my daughter upon my death, she will be more affluent. If she is more affluent, her children are more likely to be affluent. Conversely, I could have a descendent who is an alcoholic, and by coming into property, their habit could be funded to horrid extremes.

The truth is, I had been very much focused on the now. Yes: getting tattoos, writing poetry, trying to stand out and hoping that by creating something of potential beauty, my life would have some value in the eyes of my peers. Cloud Atlas has changed that, at least to an extent. Although I feel pathetic at such an admission, and rightly so, I now view my life as a link in a long, long chain. Whilst this is nothing new per se, it is a new experience for me – to take a step outside of myself, and realise I am a consequence of many forces over which I have had no control. In addition to this, I know my decisions have many consequences, not just for the present, but for future generations I will never meet.

I am worried that this seems so very obvious: but that’s what excellent philosophy does! It takes what should be obvious, and presents it in a simple way. I love quotes, so let me end with a quote from Cloud Atlas, one which I will leave to you, the reader, to muse upon.

“Fear, belief, love. Yesterday my life was headed in one direction; today it is headed in another. Fear, belief, love: phenomena which dictate the course of our lives. These forces begin long before we are born and continue after we perish. Yesterday I believe I would have never had done what I did today. I feel like something important has happened to me. Is this possible? I just met her, and yet I have fallen in love.”

Samuel Mack-Poole

Life is meaningless, right? Selim 'Selim' Talat

Life is meaningless, right?

The Philosophy Takeaway Issue 46 'Open Topic'

Let’s face it, God is dead. The only religious belief that can survive with a straight face these days is of the harmless variety. Pleasant church picnics and cultural visits to the mosque, community masses and colourful Hindu festivals -- wonderful things. If people start taking religion too seriously, eyebrows of worry start to rise, and few people really want a return to the good old days of church and state being bedfellows again (see the Dark Ages). The golden path to godly perfection and eternal bliss has been well and truly scrubbed away by the amoral brush of the rational mind. We do not know for certain where we are going after we die, and no amount of mass delusion is going to change that. The easy-ish answer of God and scripture is over. Religion is reduced to an interesting cultural antique, and a useful glue for charity-sector organisations.

Are we, then, lost in the cold cosmos with nothing to guide us? Without absolutes, are we not doomed to quarrel and strife? I would say no. Firstly, nothing causes quarrels like two groups of people both claiming to have absolute answers to absolute questions. Any debate between two fundamentalists is a prime example of this. They will never be able to find ultimate common ground and will always end up missing vital things in common. Without absolute belief we are inviting less violent disagreement, and more discussion. We can have the modesty to admit we might be wrong, and search for alternatives. This scepticism seems to be quite widespread, at least among the people I have met. An emphasis on individuals finding their own path has sprung up time and time again in my philosophical conversations. However, being able to think for yourself is not enough: being sceptical is vital to escape falsehood, yet it leads to nowhere but more scepticism. If we stay sceptical we are now confronted with a 'relativism of meaning': where reality comes down to the whims of individual people or groups, with no means to determine right or wrong outside of that, and with all views being equal in that they are ideally suited to their conditions. How do we escape relativism and anchor ourselves in something more reliable?

I think a lot of depressives could be cured of their ailments (starting with myself!) with a simple realisation: the universe is not meaningless by default. Nature is a realm outside of meaning, or meaninglessness. These two M-words are an invention of the human tongue, and should be left in the realm of the human tongue. What I am saying is that fundamentally we do not have the means to accurately depict reality from our position as individual human beings, experiencing reality from only one perspective. That does not mean reality is not out there, it just means it is beyond us; at best we can get a general idea of it. The sciences will greatly enhance our understanding of specific processes, but science is not one huge body of theory working in the same direction, but a battleground of ideas striving for supremacy, with brilliant experts on both sides clashing one against the other. There are no absolute answers in science, and there never will be. What we can find, however, are probabilities, and these provide us with the means to either improve the material conditions of our species or annihilate one another with ever-shinier weapons. We still have not completely escaped the clutches of relativism (for who do you believe when confronted with two great theories?), but at least now we are in the more comfortable territory of possibility. We don't have any absolute 'right and wrong' which exist beyond humanity, but we do have some damn good probabilities that are more than mere guesses.

Now, let us return to this notion of meaninglessness as a purely human concept. Trying to define it is a tough one. My own thoughts of meaninglessness come from the lack of permanence we are facing and the fleeting nature of our existence on this mortal span. Effectively, I am suffering from limited-time-angst. We will all someday perish, and in a thousand years few of us will be remembered. This lack of finality is rather dour, but should quantity of time be considered more than quality of it? The cosmos is vast, slowly moving through the aeons, and we are tiny specks of dust on the (insert analogy here). Our moments of love are fleeting. Our creative joy comes and goes at its own pace. We spend most of our lives in a state of dull plodding labour for the profit of pointless institutions; you dig a hole, I will fill it up. So it’s mostly quite shit. We could call our individual moments of passionate connection and artistic triumph worth the struggle. If these good things are just tiny moments of joy at least they are something quite genuine, and give us a little something to live for. Quality over quantity?

The meaning of life cannot be produced in a two page article, nor in a hundred thousand million word book written by re-arranging the stars into those queer little runes we call words. If the meaning of life could be produced in such a format, you can say goodbye to philosophy, wonder, mystery and art. All another person might be to you is a single inn on your journey, and this journey is all we are entitled to. It leads nowhere nice in the end, not unless you are something of a fetishist for being buried and devoured by hungry worms and such. It is quite funny though that meaning has to have to an end point to qualify as meaning. It seems to be a very "goal-orientated" capitalistic way of thinking, informed by our culture. In order to stick two fingers up at this aforementioned capitalist institution, with its inevitable 'go get 'em philosophy' market, I will end on this open-ended, pointless (but not worthless?) message.

There is no meaning in life, nor is there an absence of meaning. No one is going to give you any easy answers, and anyone who does is playing upon the insecurity all higher animals feel when faced with existence. Embrace the freedom offered to you by the collapse of cosmic authority by chasing artistic dreams, making the mystery a harmless way to pass your time and win a small snatch of pride in doing so. Debate and discussion must be permanent, so get stuck in and do not be afraid to stick to a solid position; if it turns out to be an improbable position, let it crumble. Forget the destination, there is none, just make the journey worthwhile and always, always try to be a kat on the way.

Selim 'Selim' Talat

Philosophy debunked: making the sensible, sensible (in 500 words or less) - Perry Smith

Philosophy debunked: making the sensible, sensible (in 500 words or less)

This is the part of the newsletter where we take a particular philosopher/philosophical theory/term and debunk it, to take it, and make it (hopefully) in some way more understandable, less wordy, but also interesting (and maybe give you something to show off to the boss/significant other with). For me, and us (at the Philosophy Takeaway), this is what philosophy is/should be, anyway (when it's not just written for: a) stuffy, dust-covered academics, to show how big their brains are - by their being able to understand and use such terms, and b) to give a reason why they're single, and most probably will die alone - by their having to spend so much time learning what these terms mean, and having none left over for a social life, which is something, again, we, at the Philosophy Takeaway, too, only know too well.

Now, without further ado, Rationalism (in 500 words or less). Rationalism is the philosophical school whereby we can simply come to the knowledge of things by the use of our logic alone. Using deductive reasoning - that is to use our intellect, we can see the truth of propositions, such as those of mathematics (like 1+1=2), but also, in some cases, of the truth of things outside this analytic (of things being true in themselves) framework, and is also extended to such things like the existence of God (this being opposed to Empiricism, whereby knowledge/truth is derived by induction- that is, acquiring knowledge from experience and the sensations we derive from the world). Because of this intellectual capability, Rationalists also believe that there are such things as innate principles (of there being things that we can know before experience), due to this inbuilt capability of our being able to find truth, without having to experience it. Another prominent feature of Rationalism, therefore, is the mind/body distinction; Rationalists, in the most part, are also Dualists, which means they see the mind and body as being two separate, distinct, things (and also view the mind as being more important), as it is through the mind that we come to know things about the world. Some examples of Rationalists include Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz; a good text to help understand Rationalism further would be Descartes’ “Meditations on First Philosophy”. And there you have it, Rationalism in 500 words or less!

And now for some Takeaway Teasers

I) Descartes takes his date for the night, a young Spinoza, to a posh restaurant, after the two of them had a falling out over Descartes’ mind/body Dualism, to make it up to him. Them both being Rationalists, they thought it best to go out, as logically, this would preclude there being any washing up afterwards, and would also allow for more time for the playing around with candle wax for the both of them. The waiter seats and hands them the wine list, with Spinoza then asking to order the most expensive bottle on the list, citing the fact that, due to their both being expressions of the same one substance, God, it would be as though, in a roundabout way, he (Spinoza) would be paying as well. To this, with a knowing glare, Descartes chortles: "I think not!", and *POOF* he disappears, leaving Spinoza the bill.

Perry Smith

Art - By Martin Prior

This weeks artist-logician was Martin Prior: http://martinse.livejournal.com/

What is logic? - By Ellese Elliott

What is logic?

Logic is hidden behind every conversation, joke, story or argument. Logic is necessary in order to be able to have an understandable form of communication. Without it, conversation, jokes, stories or arguments could not take place.

Aristotle was a famous old bloke from Ancient Greece who thought a lot about a lot of stuff, but most importantly, for this subject, he thought about thought; what it was and how it takes place. He said that thought has laws. There are rules which enable the process of thinking to happen. The most crucial law of thought is the law of identity. The law of identity states that:

A = A.

The equals sign is another way of saying the same as. Anything can be put in the place of ‘A’. For example, 'A = A' can stand for ‘that orange’ is ‘that orange’,’ you’ are ‘you’ and ‘logic’ is ‘logic’. This means that a thing is identical with itself.

The other thing that Aristotle said was that if it follows that if everything is the same with itself and that this is a law, then it cannot be a contradiction. This thought is expressed in the law of non-contradiction. It cannot be that:

ORANGE = NOT ORANGE

We cannot think this orange is both an orange and not an orange. Let’s put this in a scenario: let’s say you and your mate Kinglsy arranged to go out on the pull. You both agreed to meet outside Tottenham Court road tube station at 10:00pm.

You are standing there, it’s pouring down with rain and Kingsly isn’t there. You try calling him, but it’s forwarding to 02 voicemail and taking your last bit of credit and your thinking, ‘I hope this twat has got a good reason why I’ve been standing here for half an hour like a mug in the rain.’ He turns up causally at 11.00pm. You’re very angry, so you say, “Where the hell have you been?”

Kingsly says, “Mate, by 10.00 pm I did mean 10.00 pm, but I didn’t mean 10.00 pm and I meant 11.00pm. Do you know what I mean? “

This is an example of a contradiction and is not a reason at all, let alone a good one. When we are met with a contradiction we are just utterly confused. We have to ask, “Kingsly what the hell are you on about?” Kingsly then goes on to say some other nonsense because he has taken acid. Kingsly is no longer using the laws of identity to express himself. This raises an important point as it doesn’t matter how logical you are being if the other person is being illogical, a conversation cannot take place.

Now, it seems pretty obvious that things are what they are and are not what they are not. Therefore, when we talk about whether an object is either an orange or not orange, whether it is either 10.00pm or not 10.00pm, we are referring to the last law of thought called the law of excluded middle. An example is as follows:

I am a human being

Or

I am not a human being.

One of these statements has to be true. However, they cannot both be true or they cannot both be false. When Aristotle thought about the laws of thought thousands of years ago, he realised that human beings cannot think outside of these laws. As a last exercise, try it yourself. Can you think of an orange and not an orange, which are both properties of the same thing? Can you understand what Kingsly means by 10.00pm and not 10.00pm? Or do you think it is true that you are a human and not a human?

If you could think of any of these things you may have a hard time explaining it.....

Ellese Elliott

The Philosophy Takeaway 'Logic' Issue 45

The limits of logic: By the philosophical Prometheus, Samuel Mack-Poole

The limits of logic:

The purpose of this piece, though explicit in the title, and implicit throughout, is to argue that logic is rather limited. As such, it makes little logical sense to view the world within a narrow logical sphere.

Once, when engaged in conversation at The Philosophy Takeaway’s stall with none other than the mathematical genius that is Dmitry Dereshev, I was drawn into a debate regarding how useful emotions are. The conversation -- as far is my fallible memory can recall – went a little like this:

DD: I do not see how emotions are useful. They are, to be honest, a waste of time.

SMP: Yet, if we are forced to experience emotions, doesn’t it make sense to understand them?

Having thought about this, I have to say that the latter statement can only be true. There are a couple of trite archetypes that come to mind: firstly, we have the autistic genius. He or she can understand particle physics, but when it comes to maintaining friendships, is proved to be woefully inadequate. Conversely, we have the overly emotional artist who is so dominated by their emotion that they are blinded by it. However, if they were given something highly logical to do, they would be flummoxed.

Therefore, it is clear that when it comes to the human condition, balance is essential.

Thus, when it comes to philosophy, should we be obsessed with logic? Isn’t philosophy, by definition, about wisdom, rather than logic? If we are obsessed with logic, are we in fact illogical?

A notable example of the limitations of logic is the liar paradox. I’ve written about this before, but it is applicable in the context of this article. A liar paradox is a sentence that carries a contradictory binary truth. An example of this is as follows: All men are liars. St Jerome elaborated upon this:

“I said in my alarm, 'Every man is a liar!' "(Psalm. 116:10) Is David telling the truth or is he lying? If it is true that every man is a liar, and David's statement, "Every man is a liar" is true, then David also is lying; he, too, is a man. But if he, too, is lying, his statement: "Every man is a liar," consequently is not true. Whatever way you turn the proposition, the conclusion is a contradiction. Since David himself is a man, it follows that he also is lying; but if he is lying because every man is a liar, his lying is of a different sort.”

Moving away from the liar paradox, I’m sure we’ve all met a very persuasive sophist in our lives. I use the word in the modern, sense. A sophist can be defined as: a person who uses a specious argument for deceiving someone. In a truly modern context, one may call such a person a rhetorician. Such a person may be very skilled at making arguments. Despite the fact that the arguments are linguistically sound, they can often fly in the face of the truth.

A modern example of sophistry has been committed by Jeremy Hunt, the secretary for health. He is, of course, a member of the current Conservative-dominated government. Although the term of sophist is applicable to many politicians, Hunt’s words on the closure of Lewisham Hospital really are a shining example of sophistry. He stated that his plans will deliver “better clinical services”. This is, quite obviously, a dubious statement to make in the light of the facts. Closing a hospital in Lewisham, and then telling people to go to Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Woolwich is in no way an improvement of local services. Moreover, it seems like a harrowing example of Orwellian doublethink.

Another notable example of logic being limited is through its perfection against itself. If two opposing arguments are equally logical, what are we to think? If two of The Philosophy Takeaway’s finest philosophers wrote an essay about the ethics of advertising, with one pro-advertising and the other anti, I’m sure both could include equally logical, non-contradictory and sound arguments.

So, if we are, as philosophers, confronted with arguments that are equally logical, how do we proceed in making our decisions? It seems that life experience, intuition and emotion all play a part. Or, more concisely, we use wisdom.

A quote from Pascal -- yes the very same Pascal who (sorry for the pun) coined Pascal’s wager -- is of extreme salience in the context of this article. Pascal once stated, “The heart has reasons of which reason is ignorant.” I do wonder if emotions and logic have to be at odds. Can they not be used to aid each other, instead?

Please don’t think I have been attacking logic, as that has not been my goal. The purpose of this article has been to demonstrate the limits that logic has. If logic, however beautiful and profound, is so limited, should it be put on such a pedestal? To do so, it seems, would be unwise, and, ultimately, against the very essence of philosophy.

By the philosophical Prometheus, Samuel Mack-Poole

The Philosophy Takeaway 'Logic' Issue 45

The Board game: Social Logic - By Selim 'Selim' Talat

The Board game: Social Logic

The board game is the height of human interaction. It is the ultimate defense against boredom and blandness, standing up there with the icelandic family huddled around the fire, recounting their imaginative sagas. It is as powerful as the very idea of narratives and stories which will always remain in our human psyche. The board game, for all of it's development throughout the millennia, is nothing more than the very primitive experience of the hearth, around which are gathered friends or family. On top of all this, it is also tapping into that most fundamental human experience - intelligent games and play. A board game is a complete experience of touch, sight and smell (mmm, cardboard!). It is quite a shame taste has not yet been incorporated yet, but I am sure it is on its way. This is a combination of 'nature', here defined as direct sensory experience, and 'civilisation', the abstract higher-reasoning of logic and imagination.

You must meet the board game half way, becoming engrossed within its artificial world, for most of the time it is not given to you on a plate. Yet nothing feels more natural than immersion, that unique ability we have to turn little bits of cardboard, plastic and a few dice into something active, and dare I say it - alive. Hanging over the pieces, so simple in our world of microchips, electronics and engineering genius, are the rules. These are laws which are to be placed on top of the physical aspects of the game world like a sheet of snow. They are entirely imaginary, abstract laws which must be interpreted and then applied to make the pieces move and carry out the objectives (it's quite an obvious thing to say really, but then again my level of philosophy is often just stating the obvious!). We become so accustomed to the rules being part of the physical aspects of the game that we come to associate the knight with his leap, the queen with her multi-directional fury, the bishop with diagonality, and so on. These moves are contained not in the actual pieces themselves, but are completely separate, operating in a world of logic within our minds. Nowhere in life can we be more assured of purpose and function then upon the board, where disputes still arise, yet an appeal to logic and a powerful code of 'ethics' can be drawn upon! It is meaning itself, contained in that wood, plastic and paper - even if it is illusory.

Take this in contrast to the world of television and the video game. In front of a digital screen the rest of the body evaporates, leaving a pair of floating eyes and ears, with a disembodied hand clutching at a joypad or a remote control. If the human being is a complete entity, experiencing reality through all of its senses, with this mind-thing on top of it, then the degradation of the natural body cannot be a good way to become 'sensate' - a total bodily intelligence. This is the latest form of sociality plaguing my generation (sorry about that everyone, not that your generation was any better though - our problems are just different to yours). The faces are turned away from other human beings, hyponotised by that alluring cobra we call the screen. Millions of pounds are funnelled into each project, to feed this snake so wretched, and the more there is at stake, the less risk they will take, creating an overall taste in the video gaming world of microwaved baked beans which have been left in the fridge for too long (and have gone a disturbing shade of grey). In terms of getting the logical part of our brains ticking, there is little to be found in the digital world. That is not to say it does not exist, for there are always gems which deserve to be sought out, yet fundamentally social logic belongs more to the humble board.

Which brings us nicely along to the next point. Namely, that sociality and logic may seem like opposites; the difference between the stuffy mathematician and some form of inane socialite, but they are fused together perfectly in chess. This is the most obvious example of social logic, where the extent of seriousness and challenge is determined only by how russian ones opponent is!

If we shift out focus back onto the outside world, we can see some parallels with our chess boards, for our own world is itself a game, with its artificial laws of varying utility. To dredge up an old cliche, life is one massive (board) game, or at least it might as well be. The outcome of this game is not determined by the number of actual pieces available, anymore than putting a thousand chessmen in a pile will change anything, or mean anything. The game is determined by rules which organise how the physical pieces are arranged, and it is this arrangement which makes the game; its laws, its objectives, and all of the informal rules which accompany it (see custom). Eventually, the rules and logic of the game become nature itself, tied in to the otherwise meaningless components that make it up. Naturally, it is a game skewed in the favour of the rules-writer in real life, who will appeal to the 'always true' realms of logic and/or nature to justify themselves, but we won't go into a crypto-anarchist rant just here. The good boardgame at least is different in that the designer has to balance their creation, ideally in a way where everyone has a chance to win, sometimes individually and sometimes cooperatively, with no particular favour incurred on any party (see the bourgeois management class and their political cronies!). Perhaps then the board game is a true representation of logic, which incorporates a fairness and reciprocity (that is, a mutual exchange of one thing for another) within it, for the mutual benefit of all parties involved. You cannot, after all, truly win anything if you cheat. The useless and selfish designers of life's board game could learn a thing or two from chess to say the least.

One cannot be alone with a boardgame. Just as ideas come to fruitition when they are brought out into reality and discussed, so too do we come to life as social animals in a mutual environment. The board game staves off boredom like a ward. Imagination is what truly enriches life, drawing from a well of infinity, filling us up like protein-rich bread. It can also fuse all of this with the challenge of logic and puzzle, which other forms of interaction do provide in all fairness, yet in lesser quality and quantity.

Selim 'Selim' Talat

The Philosophy Takeaway 'Logic' Issue 45

Logic - By Martin Prior

Logic

Well, for the first time a Norfolk pine has adorned the front page of this Newsletter, and I am sure it is fitting that such a tree be considered the Tree of Logic. From any picture of one, one can see the branches pleasantly grouped, towards the top isolated branches, then a few in pairs, then threesomes and then in larger clusters the lower one gets. And so it is with logic, we add to our concepts, and likewise we must add to our axioms (self evident truths which require no proof).

We do know of course that two frownies make a smiley, as displayed at the top-most point of the Tree of Logic, and of course that it is entirely wishful thinking that two frowns make a smile, but of course two negatives do make an affirmative, when they are ‘composed’.

Now if we try and do an overview of logic, we can either survey how it has developed, or survey its applications. But if you survey its applications, you will view each at its most recent, most technical stage of advance, and you will be looking at matters of similar complexity. Such applications include mathematics, computing, language, the logic of possibility and the logic of time.

If we look at the development of logical theory, Western philosophy sees its beginnings in Classical Greece, and this includes logic, as one of the Classical trivium, which also included grammar and rhetoric. In these Classical times, such pursuits were far from trivial, and rhetoric in particular was essential for the new Athenian ‘democracy’: slavery gave the masters time to be democratic, and logic was a key weapon. Types of fallacy could be collected as an informal analysis, such as argumentum ad hominem, sustaining an argument by attacking the personality of the opponents. But then formalisms appeared, for example in Aristotle’s Prior Analytics the use of symbols for logical variables was used for the first time.

Aristotle further introduced laws such as his Three Basic Laws of Thought, which importantly included the Law of the Excluded Middle. All propositions have to be either true or false. And one of Aristotle’s most detailed systems is that of syllogisms. Maybe we should look a little bit more closely at what syllogisms are about. There are basically three key models, ‘Barbara’ ‘Dimatis/Disamis’ and ‘Daraptis’:

(I, Barbara)

(i) All X is Y,

(ii) All Y is Z,

(iii) Therefore all X is Z.

Note that if we say that no capitalist has a heart, we mean that all capitalists are heartless - or more strictly ‘non-having a heart’. Note also the formulaic convention of using ‘is’ when it will often be replaced by ‘are’. Let us capture Barbara by means of my ‘Bridge of Transitivity’:

Barbara

|

Now modern logicians will say that X need not exist, and if so, Y need not exist, and if the latter, Z need not exist either, so now we can look at our second format, where we change (i):

(II, Dimatis/Disamis)

(i) Some X is Y (Dimatis), or some Y is X (Disamis)

(ii) All Y is Z,

(iii) Therefore some X is Z.

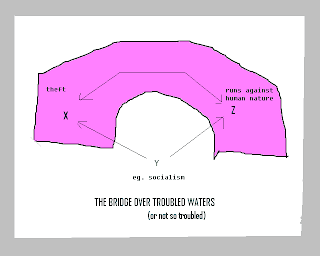

Our third basic form is Daraptis, where we have to assume that ‘all X are Y’ means that X exist, and I give the example from my previous article:

(III, Daraptis)

(i) All socialism (Y) is theft (X),

(ii) All socialism (Y) is against human nature (Z),

(iii) Therefore some theft (X) is against human nature (Z).

Daraptis

|

Now with Laws of Thought, and syllogisms, we have powerful tools in argumentation, be it logic or rhetoric, but when we look at Dimatis and Disamis, they are listed as having the same result, captured in mediaeval mnemonics by having the same vowel pattern, but this doesn’t say why some X are Y means that some Y are X in logical rather than contextual terms.

Developments appear to have lapsed, in the Christian world at least, till around 1100, with the work of Pierre Abélard, born in Brittany in 1079. According to the Stanford Encyclopaedia,

“He is, arguably, the greatest logician of the Middle Ages and is equally famous as the first great nominalist philosopher. He championed the use of reason in matters of faith (he was the first to use ‘theology’ in its modern sense), and his systematic treatment of religious doctrines are as remarkable for their philosophical penetration and subtlety as they are for their audacity.”

Despite Aristotle’s Law of the Excluded Middle, it was Abélard who introduced the doctrine of Limbo, which was accepted by Pope Innocent III. He was later a great icon of the Enlightenment and brought back knowledge of the Classical philosophers to the mediaeval world.

But anything can be examined, and maybe there is an excluded middle, making a similar deduction to Abélard when he deduced there must be a Limbo. Modern logicians say that while the Law of the Excluded Middle is taken as axiomatic, we must be on the safe side, and look to see what coherent systems will look like if we relax this assumption. Those working in Quantum Theory wish to, saying that moving particles can be neither large nor small in their size, despite the logical requirement that a particle must be either small or not small.

So we must perhaps chop off the top of the Tree of Logic:

|

|

But I for one am not sure I’m happy to saw off the branch I am sitting on...

because someone tells me it is to be on the safe side... :][

|

Martin Prior

The Philosophy Takeaway 'Logic' Issue 45

The Philosopher's City - Selim 'Selim' Talat

The

Philosopher's City

The last fortress of

indoctrination had been torn down. The last palace of authority had been turned

into a museum. The last watering hole of greed and stupidity had been abandoned

to the foxes. This was now the philosophers city. It looked much as it always

had. The rows of marble streets and Greek columns imagined in the heads of

idealists was always just a romance. Only the people inside the city were any

different. The invisible web of law and hierarchy called 'order' had changed

with them.

Homelessness

and poverty were impossible here. The doors to every house were left open (only

the individual rooms had locks). Entering without knocking would earn a dozen

disdainful looks from the current occupants. This was the law. If someone stole

from another persons complex who would they sell it to in a place where

currency was impossible? Material greed had also been knocked on the head.

Starvation

was also physically impossible. Not only had the houses been combined into

massive complexes, with numerous open kitchens spread throughout them, but the

public cafés and tea houses were always staffed, inviting passers-by indoors.

They wanted to feed people. The granaries were always looking to get rid

of their overflowing stores, and the greenhouses were free to roam; the

tomatoes to pluck, or mint-leaves to pick.

Boredom

was impossible here. If a philosopher did not have a question on their mind,

then the city would provide it for them.

And without a shadow of a doubt, everyone had the capacity to be a

philosopher. Anyone looking for a new challenge could find it quite easily.

Debates raged on street corners, a group of friends huddled in a park and

discussed their ideas, packed lecture halls filled with excitement as grand new

ideas were discussed by the more learned ones. And if the citizen was tired of

the talk and needed grittier work, there were a thousand and one unskilled

tasks that needed doing.

A

workshop could easily be booked and materials acquired, the labs were

looking for geniuses and technicians alike, the larger farms and factories

outside the city were run by people looking for a break from it all. New skills

were always waiting to be learnt, and it was not hard to find the confidence to

acquire them in such an encouraging environment.

This

was the philosophers city, and nothing was banned, for there was no authority

to ban it. Life's urges were channelled, like bubbling water through careful

canals. In the Beirut quarter dancers would fling and eroticism would

flower, honey-wine flowed by the gallon and pigs dripping in fat spun on their

flaming spits. Shamelessly they explored their perversions and their pleasures.

Naturally

this repulsed those in the Epicurean quarter (known as the garden of the

city), who removed themselves from the more visceral aspects of life. Not

because they found the rampant desire-chasing immoral, but they considered such

desires to be harmful to their state of happiness. Here the plainer

epicureans could live in contentment amongst the like-minded, conducting

experiments of both thought and science in their quest for knowledge, and

flowering in gentle creativity and self-exploration.

In

the Warriors quarter, leaders and authoritarians were hunkered over

chess boards and wargames, commanding illusory armies across bloodless

battlefields. Tournaments were rife, alliances and rivalries bloomed, tribes

and clans forged and fell apart. The soldiers sparred with foam weapons and armour,

each striving to become a master of their art. When the moon was high and the

(digital) wolves howled, they would take to the field beneath their home-made

banners and play at war. Violence was moved to an unreal plane, and violence

outside it became impossible.

Then

there were the 'wilds', dominating the least populated quarter of the city. You

did not tread too deep into this forestland without your enthusiastic guides,

for bears lurked among the overgrown brush and scrub-land, and the howls of a

fox by moonlight could scare a city-lubber out of their wits. To make fire here

required skill, to make shelter a different form of intelligence, to eat a

patience for berries and seeds. Harder still was the discovery of meaning, here

in the forest where the sky was obscured and the perceivable world shrunk down

to the inside of a wooden nut.

And

that was it. Was there a single essential thing the philosophers city was built

upon? I would not dare to say. Yet if I had to guess, it would be this

realization: that everything around us today is the result of an idea. This

means it is changeable. We are already living in someone else's utopia (and

it is usually the utopia of someone rich and powerful, shaped to fulfil their

own sense of self-importance). This order is not inevitable, and not built on

anything natural. For there is no utopia

in our nature, only the way of the hunter, which for so long was nestled in the

gaian bosom, doing what it could to survive. We can neither call our nature

good nor evil, for these moral values come much later. Nor can we paint the

natural state of mankind with the utopian brush of nostalgia.

It

is culture that is the true creator of our world. The values surrounding

us, that have become invisible through their absorption into our routines, are

just that - artificially created values. Physical processes of the body we

think manifest themselves in inevitable 'evil' ways, can actually be

channelled, and the darker side of our nature can be controlled, once and for

all.

Selim 'Selim' Talat

The Philosophy Takeaway 'Utopia' Issue 44

Utopia: the route of all evil? - By the one and only Samuel Mack-Poole

Utopia:

the route of all evil?

“The lack of money is

the root of all evil.”

George Bernard Shaw.

“But no perfection is

so absolute, that some impurity doth not pollute.” William Shakespeare.

Utopia is commonly

defined as: “An imagined place or state of things in which everything is

perfect. The word was first used in the book Utopia (1516) by Sir Thomas More.” For me, this is such a redundant

definition. I would go so far as to say that I intellectually loathe it. I

cannot fathom how a society can be perfect by any objective criteria. My

contention -- or beef – with utopia is that it is, by its very nature,

subjective. As a consequence, utopia,

even as an ideal, cannot exist in an objective sense. I have used this phrase

many times, but it really applies: the only utopia that can exist is one which

is determined by mass shared subjectivity. As a consequence, only a utilitarian

utopia can exist as an ideal, let alone in reality.

If

we think about it, one man’s utopia is another’s hell. An Islamist would love

to see a one-world government with sharia law implemented. A neo-Nazi would

detest such a world, and would want a racial divide instead. I could go on ad nauseam, but I won’t. The point is abundantly clear, isn’t it?

As humans are diverse, their conflicting utopias can only result, ultimately,

in an extreme. That extreme is war.

Many

people are willing to fight, and to die for their utopia. Marxists, Nazis,

Christians, Hindus, Jews and many other groups have done so, all too gladly. “War,”

as Trotsky said, “is the locomotive of history.” As a result, utopia is probably only going to

self-actualise through mass bloodshed, as revolutions are seldom peaceful. That

said, Ghandi’s strategy of passive resistance obviously contradicts this, but

this is very much the exception to the rule.

Consequently,

we have to ask ourselves: is utopia is the route of all evil? I think that is

for you to think about, rather than for me to say.

I

would prefer it if Ghandi’s strategy would allow my utopia to become a reality, but I doubt the world’s nations will

destroy fiat currency, and throw away their nuclear arsenals any time soon.

But, Samuel, I hear you cry, what is your utopia?

As

depressed as I am with the current situation -- perhaps I have been staring

into Nietzsche’s abyss for too long -- I still have hope. My hope for humanity is that it embraces the

ideas of Jacques Fresco. Personally, I think philosophy is at its best when it

actively tries to change the world, rather than merely analysing it. I am quite

aware that I have paraphrased a Marxist quote, but in this case the quote

serves the purpose of going beyond Marxism. I’m referring to The Venus Project, which has been

criticised as utopian.

It

is easy to see how sick mainstream society is when utopia is now a pejorative

term. Surely, we should think of utopia as something to strive towards, rather

than an ideal to mock and scoff at?

The Venus Project is extremely

provocative to any philosopher, as it is filled with egalitarian and revolutionary

values. The reason The Venus Project is so revolutionary is due to the fact that it

wishes to replace the current situation with an economic system in which goods,

services, and information are free. But,

Samuel, isn’t that communism? No, it’s not. Communist countries still

employ state capitalism. In a RBE (resource based economy) there are no nuclear

weapons, no banks, no money, no military, no suppression of technology, and no

‘charismatic’ personality cults. It’s also supremely technological, utilising

bleeding edge technology that would make fossil fuels redundant, and

advertising wouldn’t occur as there wouldn’t be any competing products. It’s

rather odd, I concede. However, it’s only odd because we’ve been indoctrinated

to believe no society can function without money, and that greed and

‘competition’ are the only true motivators.

I

can’t do The Venus Project justice in

a mere couple of pages. All I can say is that according to my thought

processes, it is worthy of merit, and, therefore, further investigation. If you

value life more widely than the paradigm of money, working 9-5, and package

holiday deals, then have a genuine look at what a RBE can offer you. For me,

its tenets are altruistic, and nothing can be more profound than the love you bear

your fellow man or woman.

If

you whole-heartedly reject the ideas of Nietzsche’s (not so) Ubermensch, Ayn Rand’s love of selfishness, the basic corrupt global lottery

of quality of life, and think that

capitalism is inherently evil, I suggest you get acquainted with Jacques

Fresco.

What

can you conclude, if anything, from reading this article? I would say the

lessons which can be learnt are threefold; utopia doesn’t exist in an objective

sense; competing utopias may lead to misery; my utopia, based on Fresco’s

ideas, is extremely meritorious. I do

feel, however, that this article shouldn’t end with my words. We started with

Shaw, so we should end with Wilde, who was a philosopher, amongst other things.

“A map of the world

that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out

the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands

there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the

realisation of Utopias.”

―

Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man under

Socialism.

By the one and only

Samuel Mack-Poole

The Philosophy Takeaway 'Utopia' Issue 44

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Want to write for us?

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, please contact thephilosophytakeaway@gmail.com